As of Fall 2023, more than 52 million students were enrolled at public schools throughout the United States. 1 Over a school year, students incur a series of expenses for school meals, bus passes, after-school programs, and technology and materials needed for class, among other costs. As the broader payments ecosystem continues shifting towards more digital options in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, school districts are increasingly contracting with payment processing companies to provide an avenue for families to pay school-related expenses online. While convenient for both families and school districts, electronic payment options present new costs and challenges for the families using them.

For example, in many schools, families can electronically load funds into an account that students can draw from to pay for school meals. Although federal policy specifies that schools must provide a fee-free option for school lunch payment, many payment processors charge a transaction fee each time a user electronically adds money to a student’s school cafeteria account. 2 Payment processing companies have broad control over fee rates, though payment companies maintain that school districts have the opportunity to negotiate these rates during the contracting process. Some districts cover part or all of this fee, but it is frequently paid by the families who make electronic payments. Over the course of a school year, transaction fees for electronic payments in and outside of the lunchroom can significantly increase a family’s total spending on school-related costs and may disproportionately impact families with lower incomes. 3

To better understand the emergence of electronic payment processors in K-12 schools, the CFPB analyzed publicly available information from the 300 largest public school districts in the U.S. and held unstructured interviews with public school officials and companies offering these payment platforms. The sample of school districts covers more than 16.7 million students across more than 25,000 schools. This spotlight highlights average costs and potential risks for families using electronic payment platforms to add money to their child’s school lunch account and reviews the market size and landscape of companies offering them, building upon initial observations referenced in the Fall 2023 edition of Supervisory Highlights. 4

As digital payments have become increasingly popular across sectors, more and more school districts around the country are offering parents and caregivers the ability to pay school-related expenses, including for field trips, athletics, and school lunches, online. 5

Families can typically access online payment portals through a link on their school district website, or through the company’s own webpage or app. Depending on the district, schools may partner with one payment processor for all electronic payments or may have one platform for school meal payments, for example, and another for other school-related payments.

School districts contract with third-party payment processing companies with the expectation that they will lower school district processing costs and increase administrative efficiency, accuracy, and security. 6 For example, digital payment information can automatically be integrated with student information, potentially minimizing errors from manually applying funds to a student’s account balance. Many payment processors also offer electronic solutions that purport to lessen administrative burden on school district staff, such as automated messaging features to parents and caregivers about unpaid academic fees or negative lunch account balances.

Despite these perceived benefits, there are also risks related to accepting electronic payments. For example, families typically have to pay fees to make electronic transactions or may have difficulty accessing timely refunds of unspent funds. Some school districts may also limit their acceptance of other payment methods like cash, even though the ability to make cash payments may remain preferable or necessary for some families. 7

Due to both the administrative efficiencies offered by online payment platforms and the high volume of daily transactions, school lunch programs present a clear opportunity to explore online payments in K-12 schools. This issue spotlight primarily focuses on the companies processing electronic payments for school lunches and the potential risks they pose to school districts and families.

Most public schools participate in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP), which are both federally assisted meal programs from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) that provide low-cost, or free meals to K-12 students. 8 Each day, on average, 19 million students participate in the free lunch program, 1.1 million in the reduced price lunch program, and 8.5 million in the full-price lunch program at public and private schools throughout the country. 9 Families with incomes at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty line are eligible for free lunch, and those with incomes between 130 and 185 percent are eligible for reduced price lunch. 10

Participation in the free and reduced price meal programs may not always fully reflect a student’s ability to afford food or cover the number of meals needed in a day. 11 As such, students who need lower-cost lunch options but do not participate in the free or reduced price meal programs as well as those who receive free or reduced price meals may still need to pay for food at school, potentially using a payment platform.

Nationwide, the average price of a middle school lunch is $3.00, or $0.40 for those participating in the reduced price lunch program. 12 A family with two children paying full price for lunch at school every day can expect to spend, on average, $1,080 on school lunches over the course of a school year. 13 Given these averages, and daily participation in the NSLP, the CFPB estimates that participating schools across the country are paid approximately $26 million every day and $4.68 billion every year by families purchasing their child’s first lunch. 14 Schools may be collecting more as students purchase additional meals or a la carte items.

The school district’s “school food authority” (SFA) manages its school nutrition program and determines what payment options are available to facilitate these transactions. 15 While there is no official market-wide estimate, one payment processor estimated that as many as a third of students at school districts with an online payment processor pay for lunch using funds electronically loaded to their account. 16 Interviews with school district administrators suggest that online payment options are popular among both families and school districts for their perceived security and convenience. 17

Nonbank covered persons, including online payment processors, are generally subject to the CFPB’s regulatory and enforcement authority and must comply with federal consumer financial protection laws. 18 Particularly relevant is the Consumer Financial Protection Act’s prohibition of unfair, deceptive, and abusive practices. 19 The CFPB’s Fall 2023 edition of Supervisory Highlights noted that certain covered persons maintained online school lunch payment platforms, and that certain practices related to the platforms may not comply with federal consumer financial protection laws. 20 Although local rules and state laws may govern types of school-related purchases, other aspects of federal law are also relevant to school lunch payments.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) has long established that children participating in school nutrition programs “shall not be charged any additional fees” for the services provided in conjunction with the delivery of school lunch benefits. 21 In this policy, the USDA specified, “by charging fees in addition to the regular reduced price or paid meal charge, a school is limiting access to the program and imposing an additional criterion for participation.” 22 In 2014, the USDA published a policy memorandum that specifically addressed online fees in school meal programs, stating that school food authorities can charge a fee for online services, but only if they also offer a method for households to add money to the account that doesn’t incur any additional fees. In the policy, the USDA suggests that schools accept money at the school food service office or cash payments at the point of service as fee-free options. 23 In 2017, the USDA issued another policy reiterating this requirement and stating that school food authorities cannot exclusively use online payment systems. 24 The 2017 guidance also requires school food authorities to notify families of all available payment options, including any associated fees. In the last seven years since the USDA published this guidance, the popularity of digital payments has grown significantly across sectors. 25

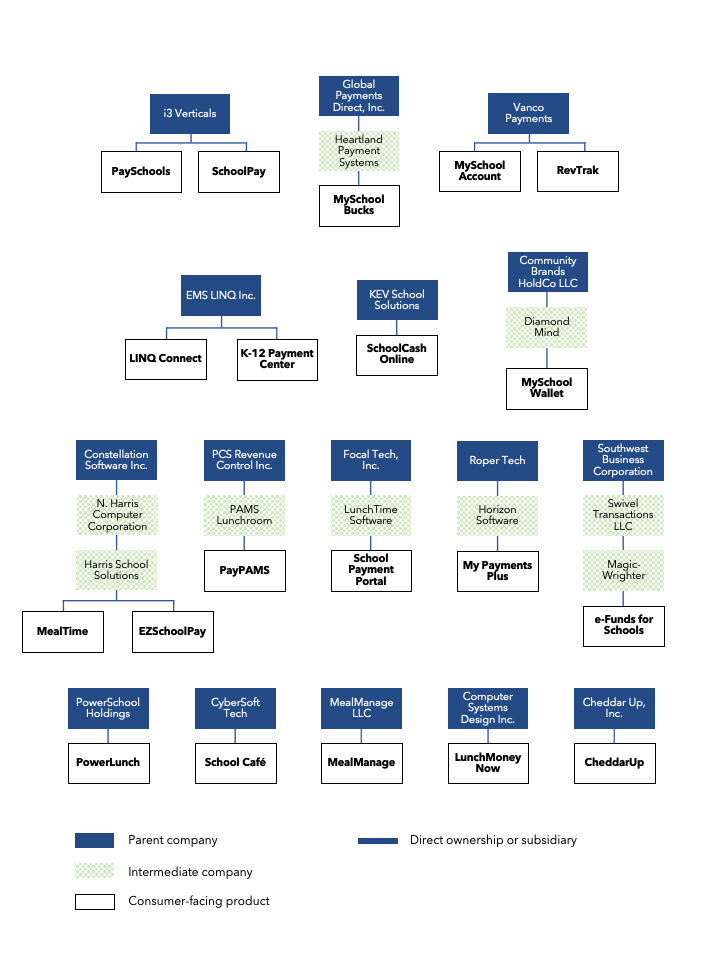

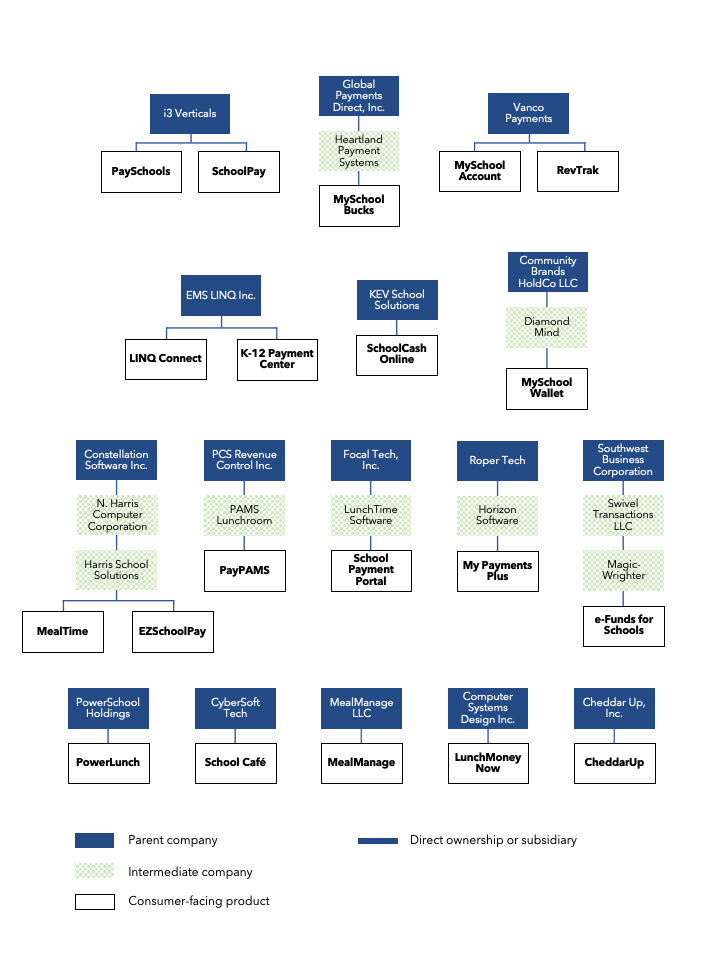

The market of K-12 payment processors overlaps with two related industries: general payment processing and student information management software. Broadly, the top K-12 payment platforms are offered by subsidiaries of large financial institutions and by companies specializing in comprehensive student data management software. Among companies that specialize in school lunch payments, the same parent holding company may operate multiple payment platforms (see Figure 1). In recent years, many smaller companies offering the same services have been acquired by larger firms or have begun offering compatible products.

Many school payment processors, which may appear to occupy a niche industry and may lack broader name recognition, are owned by, or serve, significantly larger institutions with robust revenue streams and compliance capabilities. 26 Eight of the 20 K-12 payment processors identified by the CFPB are affiliated with larger companies that offer multiple school lunch payment products, creating a potentially misleading sense of product variety and market competition. 27 Generally, the leading K-12 payment platforms are well connected to large companies in the payments and financial services sectors. For example, five are operated by independent sales organizations 28 that provide payment processing services and generate revenue for Wells Fargo, a company that is also dominant in the higher education payments market. 29

School districts enter into contracts with payment processors to help manage a number of financial and administrative responsibilities. In addition to providing user-facing payment portals, many payment processors also provide back-end services like point-of-sale software for school cafeteria systems, HR management systems, and student information systems for collecting applications for free or reduced price lunch. All these services are typically acquired under one contract, which determines what the school district pays for the services provided.

User-facing payment platforms are governed by these contracts, which also set the rates for fees charged to end users. Unlike other elements of these larger contracts, school districts typically do not have to pay to enable electronic transactions via an affiliated payment platform. Since payment processing companies have a fee-based revenue model, much of their revenue comes in the form of transaction fees.

Although school districts may experience cost savings or efficiencies of their own when contracting with processors, those financial benefits are not usually passed directly to families. Transaction fees are sometimes fully paid by a school district. 30 The USDA has a policy explicitly allowing school districts to cover transaction fees on families’ behalf using the funds in their nonprofit school food service account. 31 However, transaction fees are more commonly paid in part or full by families themselves. 32 The CFPB did not encounter any examples of school districts paying for payment processing services, except through these transaction fees, nor any examples of school districts receiving revenue from the fees that payment processors charge. 33

For many districts, the back-end software may be the main consideration when choosing a company to contract with. When this happens, a user-facing payment platform comes as part-and-parcel of a larger school nutrition program management system, insulating payment processors from competition based on transaction fees and negotiation that could lower fees assessed on end-users. Since payment platforms are typically provided without any up-front costs for school districts when included as part of a larger contract, school districts are not incentivized to prioritize low rates on fees that they will typically, in part or whole, pass on to end users. Families are only able to use the payment platform that their district has chosen, making it impossible to shop around for lower fees.

School districts that try to minimize fees charged to families may also run into challenges. Many districts may be limited in which payment options they can provide, due to cost or resource constraints that incentivize choosing providers who ultimately charge fees to families. Negotiating with payment companies may also be difficult for school districts. Although two school districts published information online about successfully negotiating with a payment company to offer a lower fee rate, 34 in interviews school officials at several districts across the country expressed that they were unaware that they could negotiate fee rates or otherwise felt that fee rates were non-negotiable. 35 Negotiating power may also vary by school district, as large districts may have additional leverage with payment processing companies or may benefit from fee discounts based on higher overall transaction volume. Smaller districts may not have the same advantages.

Most companies that enable electronic school lunch payments advertise additional features for users, including scheduling automatic payments, sending low balance alerts, sharing account balance and meal purchase information, and processing payments. Some payment processors also provide a space in their user portals for schools to upload monthly lunch menus or post other announcements for caregivers to review. For many districts, families also use these online portals to submit applications for the free and reduced price lunch programs. Apart from making electronic payments, companies promote many of these features as free with the creation of an account. 36

Payment processors typically charge transaction fees each time an electronic payment is made. Companies that process school lunch payments may also charge other fees like convenience fees, which may include a fee for transferring funds between student accounts, or annual program fees that increase the cost of making online payments. 37

As previously discussed, fee rates are determined by each school district’s contract with the payment processor. Interviews with school district officials and information published on school district websites suggest that companies have broad control over fee rates. 38 Payment processors’ terms of service also establish the company’s unilateral control over fee levels and its ability to change them at any time. 39 School districts that cover all transaction fees on behalf of their users may pay more favorable fee rates compared to individuals. At least one school district entering into a contract with MySchoolBucks received certain fee discounts after indicating that the district planned to cover all transaction fees. 40

Electronic transactions incur costs for payment processors. These costs differ depending on which payment mechanism is used. On their online portals, payment processors typically offer credit, debit, and prepaid cards, and, in fewer cases, Automated Clearing House (ACH) transactions. 41 Typically, processor’s payment processing costs fall around 1.53 percent of a total transaction for credit, debit, or prepaid cards, 42 and between $0.26 and $0.50 per transaction for ACH transfers. 43 Nonetheless, even the lowest transaction fees assessed by payment processors in school districts observed in the CFPB sample ($1.00 or 3.25%) 44 are significantly higher than the payment processors’ costs of processing electronic transactions.

In a sample consisting of the 300 largest public school districts in the United States, 45 261 school district websites disclosed a partnership with a payment processor for school lunch payments. Once a partnership was identified, the CFPB recorded a number of variables including information about associated fees, fee types, and amounts (see Appendix A).

Three providers, MySchoolBucks, SchoolCafé, and LINQ Connect, are the largest school payment processors in the sample according to the number of school district partnerships, school partners, and related total enrollment (see Table 1). In the sample, these three providers served more than 9.2 million students across more than 13,500 schools and 181 public school districts. MySchoolBucks is the largest across all three metrics, with almost 100 school district partnerships and more than 5 million enrolled students within the sample.

Sample Total

While USDA guidance requires that families are notified about available payment methods and associated fees, many school districts do not publish information related to fees on their websites. 46 Across the 63 school districts in the CFPB sample that do publish fee specifics, average transaction fees were $2.37 for flat fees, and 4.4 percent for percentage fees. Median fees were $2.49 and 4.5 percent. Since these figures are from only the 21 percent of school districts in the CFPB sample that publicly report fee amounts, they may misestimate the true market average.

In the CFPB sample, payment processors at more than 70 percent of the districts that publish fee information charge flat transaction fees. At around 25 percent of these school districts, payment processors charge percentage fees, and a much smaller portion have a transaction fee model that incorporates both a flat per transaction fee and a percentage fee that varies based on deposit size. 47 Overall, fee levels vary widely between providers, and for the same provider across different school districts (see Table 2).

NA appears where fee data was not observed.

Flat fees observed in the CFPB sample ranged from $1.00 to $3.25 per transaction. 48 The highest flat fees observed were from school districts partnering with MySchoolBucks ($3.25) 49 and EZSchoolPay ($3.00). 50 Percentage fees ranged from 3.25 percent to 5 percent of the total deposit. The highest percentage-based transaction fees were observed at school districts partnering with SchoolCafé (5 percent). 51

In addition to transaction fees, some school district websites also mention other fees that may increase the total cost for families using these services. It is unclear whether school districts are able to negotiate these fees in their contracts.

Online payment platforms offer convenient solutions for school districts and families, but they also present potential negative implications for consumers. School lunch costs can be a challenge to families across the country, in part illustrated by the national average meal debt of $180.60 per child, per year. 56 Families, particularly those that are struggling to cover the cost of lunch itself, may find it difficult to avoid fees and may face other difficulties exacerbated by the use of payment platforms.

Although payment platforms often perform a variety of services for school districts, including certain functions that help enable compliance, companies leave it to school districts alone to create and, in many cases advertise or disclose, any fee-free payment methods. Some school district websites note that families can add funds in person or by sending cash or check with a student. 57 Other school districts have policies that limit the use of cash, personal checks, or both, 58 which may raise questions regarding the districts’ conformity with USDA policy. 59 Even if families are aware of alternative options for paying school-related expenses, they may also potentially come with their own costs and limitations, in the form of transportation costs or difficulty accessing financial services. 60

Even where school districts allow fee-free payment options, free methods may not be meaningfully available to all families. Although school districts are required by USDA to provide fee-free methods and to inform families of their options to pay for school lunch, 61 not all school districts make the information readily available to families on their website. School districts are also not required to provide comparable online payment options that do not incur fees. As a result, other payment methods may be less well-known and less accessible than online payments. For non-meal-related expenses, the CFPB did not encounter any examples of similar requirements, so families may not have any fee-free options for paying these other expenses.

It may also be difficult for families to predict the total cost of using an electronic payment option. In many cases, the first time a caretaker will see how much they must pay to use an online payment platform is at the point of sale, which obscures the total cost until near the end of the transaction. Only 21 percent of sampled school districts explicitly disclose the fees associated with online transactions and no payment processors in the sample include specific information about potential fees on their website.

In some cases, families may be paying fees for electronic payments without knowing that they are entitled to fee-free options. The CFPB’s Fall 2023 edition of Supervisory Highlights noted that payment processors have maintained payment platforms on which consumers may have paid fees that they would not have paid had the consumers understood that they were entitled to free options. As a result, the CFPB observed that the payment processors’ practices may not have complied with consumer financial protection laws. 62

Many payment processors allow users to turn on automatic payments at scheduled intervals or when school lunch account balances fall below a certain threshold. Conversations with school district officials described certain issues faced by families who set up autopay and then had difficulties canceling or otherwise forgot to cancel it when no longer needed. 63 Excess funds can quickly accrue in a student’s school lunch account if automatic payments are accidentally left on. 64 Each automatic transaction still incurs a per-transaction fee assessed by the payment processor, so families using automatic payments may be paying additional per-transaction fees to add unnecessary funds. Families are instructed to go directly to their child’s school for refunds, so any extra funds paid into a student’s school lunch account create additional administrative tasks for school district staff and may further delay when a refund is ultimately received.

At the end of an academic year, funds in a student’s lunch account generally roll over for use when the school year resumes in the fall. There may be times, however, when families need to request a refund of the funds paid into their student’s lunch account. Terms and conditions of payment platforms generally note that if a caregiver is seeking a refund from a student’s account, they must contact their child’s school directly. 65 Payment processors do not hold on to student lunch account funds, as funds are directly transferred to school district bank accounts once a payment is made. Each school has its own process for distributing refunds. 66

At some school districts, the refund process can be complicated, requiring additional paperwork for families, 67 and may take weeks for the money to be returned. 68 Families using these payment platforms may be less willing to add a substantial amount to their accounts, due to the difficulty of accessing refunds, which may result in incurring additional per-transaction fees.

Fees charged by payment platforms affect all families, though low-income families may be disproportionately impacted depending on the fee type and how often they make deposits over the course of a school year. Based on sample averages, school lunch payment processors nationwide may be collecting more than $100 million each year in transaction fees alone. 69 The total fee revenue collected by payment processors could be higher, after including revenue from other fees or additional lunchtime expenses. For families paying for their child’s lunch, these fees may pose a significant additional expense.

Flat transaction fees, as opposed to percentage fees, are much more prevalent among sampled school districts. By nature, flat fees have a regressive impact on lower-income users. Payment platforms appear to charge the same transaction fee for all users, regardless of whether a student receives free or reduced price lunch. Flat transaction fees are also much more expensive for users who make deposits more frequently, compared to those who can afford to deposit more money less frequently. 70 An industry-sponsored survey found that 60 percent of users on online school payment portals make two or more deposits per month, amounting to approximately 18 deposits per year. 71 Conversations with school district administrators suggested that some families may be using these online services much more often, up to once a week. 72 Although some families are able to deposit significant amounts into their child’s account at the beginning of a school year, that option might not be available for families living paycheck to paycheck. Frequent deposits can exacerbate the regressive effect of flat fees for families who do not have the financial flexibility to pre-load hundreds of dollars into their child’s lunch account at one time.

Table 3 shows three scenarios of potential fee burdens associated with full-priced school lunch costs. The below scenarios are based on two different levels of deposit frequency (twice per month, or biweekly, and three times a year), the average flat and percentage fee rates from the CFPB sample ($2.37 and 4.4 percent), the average full-price cost of a middle school lunch ($3.00), 73 and the average length of a school year (180 school days). 74

$2.37 fee, paid biweekly for a school year

$2.37 fee, paid three times a school year

4.4% fee, paid over the course of a school year

Families who pay full price for school meals and make two deposits a month into their child’s lunch account would incur over $42 in fees over the course of a school year. For these families, for every $1 they spent on school lunch, they paid $0.08 to the company processing their payments. Families who instead make just three payments a year end up paying much less in fees, around $7. In this case, for every $1 spent on school lunch, they paid just over $0.01 to a payment processor.

Table 4 shows three scenarios of potential fee burdens associated with reduced priced lunches, which cost $0.40 per lunch on average. 75 Since transaction fees appear to be the same across the board regardless of whether a student is eligible for free or reduced price lunch, families who pay for reduced price lunch pay more in fees relative to their school lunch costs during a school year.

$2.37 fee, paid biweekly for a school year

$2.37 fee, paid three times a school year

4.4% fee, paid over the course of a school year

Families who pay for reduced price lunch and make two deposits a month into their child’s school lunch account would still incur over $42 in fees over the course of a school year. For these families, every $1 spent on school meals for their child corresponds to $0.60 that was paid to a payment processor. Families who can afford to make just three payments a year still pay $7 in fees, which amounts to about $0.10 for every $1 paid for school lunch.

Every day, families of school-aged children across the country spend millions of dollars on school lunch. Many caregivers opt to use online platforms to deposit money into their children’s accounts, incurring average fees of $2.37 or 4.4% of the total deposit per transaction. These fees are widespread, regressive, and may be burdensome for families and districts, who have little control over fee rates and few opportunities to shop around.

School food authorities participating in the USDA’s National School Lunch Program are required to provide fee-free avenues to pay for school lunch and inform families about all available payment methods, including associated fees. However, these fee-free options are not always well advertised or accessible. Despite requirements from the USDA, families may be paying more in fees than they would choose to if they had access to comparably convenient payment options with lower or no fees. Although school districts are able to negotiate fees while contracting with payment platforms, payment processors appear to have broad control over the fees they charge. Few school districts have been successful in ultimately lowering fees for families.

School districts face limited options. The market for school-related payment processing is dominated by a few market leaders and school food authorities may be locked in to using a certain payment platform due to its connection to the back-end service managing their school nutrition program. In turn, families have little choice in the payment platform offered by their school district and may be particularly vulnerable to harmful practices, including those that may violate federal consumer protection law.

This report analyzed data from the 300 largest public school districts by enrollment according to Fall 2021 data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). 76 The CFPB examined the website of each school district in the dataset to identify publicly available information on lunch payment processor partnerships and fees. The CFPB also searched the websites of associated payment processors. This research was conducted between December 2023 and April 2024.

Once a school district was identified, the CFPB recorded the URL for the relevant district website, whether a payment processor is used for online school meal payments, whether the district offered free lunch for all students during the 2023-2024 school year, whether there is a fee associated with online payments, the fee category (e.g., flat fee or percentage), the fee amount, and relevant URLs. School districts within the sample that use only alternative channels to inform families of online lunch payment options, such as direct-to-family newsletters or printed resources distributed at the beginning of the school year, are not adequately captured in this dataset. Only cases where a payment processor for school lunch payments could definitively be identified are observed in the sample.

The CFPB also included descriptive statistics for each school district in the sample, including public high school graduation rates, total number of English language learners, the share of students eligible for free or reduced price lunches, the poverty rate of 5-to 17-year-olds within the district, and the number of schools for each district. For the sample of the 300 largest districts, this data comes from the National Center for Education Statistics. 77

Table 5 contains a comparison between descriptive statistics of the CFPB sample and public school districts nationwide.

Number of K-12 schools

Number of school districts

Average school district enrollment

Average school size

Average share of students eligible for free and reduced price lunch program

NA appears where a calculation is not applicable.

The CFPB sample, which includes data from the 300 largest school districts by fall 2021 enrollment, is not representative of the full population of public schools across the country. The CFPB dataset overrepresents large school districts, with the sample average school district size (55,782) far exceeding the national average (3,484). According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, 71 percent of school districts in the U.S. had fewer than 2,500 enrolled students in the fall of 2021. However, these schools serve just 16.7 percent of the total number of enrolled students nationwide. The CFPB sample captures 36.1 percent of total student enrollment, while featuring only 2.25 percent of school districts. The CFPB dataset reflects nationwide trends for the percent of students eligible for free and reduced price lunch at about 48.5 percent.

In addition to the sample of the 300 largest school districts, the CFPB also analyzed data from a sample of 50 rural 79 public school districts, selected randomly from all U.S. counties with a nonmetro 2023 Rural-Urban Continuum Code (RUCC), 80 then subsequently matched with a corresponding district. 81 This rural sample was used to verify that smaller school districts, serving fewer students, also use these payment products for school lunch costs. Figures from the rural sample were not used to generate fee ranges or averages reported in the body of this issue spotlight. Among 50 rural school districts, 29 disclose a partnership with a third-party payment processor. MySchoolBucks is also the largest provider in the rural sample with 8 district partnerships. The rural sample is not large enough to analyze other information, such as fee averages.

To generate Figure 1, the CFPB identified 20 lunch payment processing platforms in use at public schools in the United States. The CFPB gathered an initial list of platforms by searching for key words and phrases (including “online school lunch payment,” “lunch payment platform,” and “pay lunch online”) and examining the first five pages of search results. Platforms discovered through the construction of the school district sample (see Appendix A) were added to the list. The CFPB initially identified 26 platforms through these data collection methods. The CFPB then validated the list by, for each platform: (1) noting any public marketing statements by the processor or related companies confirming that they serve U.S. public schools; (2) finding U.S. public school districts that confirm usage of the platform on their websites; and (3) identifying any mergers or acquisitions with other platforms. The CFPB removed platforms that were not confirmed to serve U.S. public schools or have been merged into other existing platforms, paring the list down to 20 platforms. The CFPB then analyzed the ownership structures of the payment platforms to identify their parent and affiliate companies, both through examining their websites and the public securities filings of related entities.

EMS LINQ, Inc. owns two payment platforms that the CFPB identified—LINQ Connect, the third largest platform in the CFPB sample, and K-12 Payment Center. 82 The CFPB additionally found two lunch payment processors that have been consolidated into LINQ Connect: Titan, which EMS LINQ acquired in a $75 million leveraged buyout in 2020; and MealsPlus, which was previously marketed as a “LINQ solution” but merged into LINQ Connect in 2021. 83 Some school district webpages and public resources continue to use these older product names, and as of February 2024 the website of MealsPlus continues to exist, though most of its buttons redirect to LINQ Connect. In its public marketing materials, LINQ claims to serve 30 percent of U.S. school districts through its suite of K-12 business products. 84

Additionally, Constellation Software Inc., a Canadian conglomerate, owns N. Harris Computer Corporation, which owns Harris School Solutions, which operates two platforms: MealTime and EZSchoolPay. 85

Five of the payment platforms identified by the CFPB are registered ISOs of Wells Fargo. These platforms include: MySchoolBucks, (a product of Heartland Payment Systems and a subsidiary of Global Payments Direct, Inc.), 86 PaySchools and SchoolPay (products of i3 Verticals), and MySchoolAccount and RevTrak (products of Vanco Payments). 87 Heartland Payment Systems is an ISO of Wells Fargo and the Bancorp Bank, and Global Payments Direct, Inc. is an ISO of Wells Fargo and BMO Harris Bank. i3 Verticals is an ISO of Wells Fargo, RBS Worldplay, Deutsche Bank, Merrick Bank, BMO Harris Bank, and Fifth Third Bank. 88 Vanco Payments is an ISO solely of Wells Fargo. 89

The remaining 11 platforms identified by the CFPB do not appear to belong to companies offering multiple K-12 lunch payment processors, but many are owned by subsidiaries of large, publicly traded holding companies or marketed as part of a suite of K-12 information management products. Cybersoft Technologies owns SchoolCafé. 90 Roper Technologies, a publicly traded software and technological holding company, owns MyPaymentsPlus. 91 PCS Revenue Control Systems, a tech company specializing in K-12 nutrition software, owns PayPAMS. 92 Community Brands HoldCo LLC, a cloud-based software conglomerate, owns MySchoolWallet. 93 FocalTech, Inc., an information technology and e-commerce services provider, owns School Payment Portal. 94 Southwest Business Corporation, a diversified financial services company, owns e-Funds for Schools. 95 Computer Systems Design, Inc., a food and nutrition management software provider, owns LunchMoneyNow. 96 KEV Group, an international school activity fund management company, owns SchoolCash Online. 97 Two separate, independent companies named after their products own MealManage and CheddarUp. 98 Finally, PowerSchool Holdings, a publicly traded comprehensive K-12 software company, owns PowerLunch. 99